Episode 061 Eight Artists

Show Notes

We are closing out 2022 with highlights from eight incredible artists that graced the show this year. Tune in to hear the voices of Gary Hill, American Artist, WangShui, Meriem Bennani, Alan Michelson, Tourmaline, Arthur Jafa, and Hito Steyerl discussing how they think about the preservation and documentation of their work, as well as intimate inside glimpses into their practice and studios. Sending a huge heartfelt thanks to everyone all of the listeners that made 2022 such a memorable year for the show – wishing you all the best and see you in the new year! xo

Get access to exlusive content - join us on Patreon!

> https://patreon.com/artobsolescence

Join the conversation:

https://www.instagram.com/artobsolescence/

Support artists

Art and Obsolescence is a non-profit podcast, sponsored by the New York Foundation for the Arts, and we are committed to equitably supporting artists that come on the show. Help support our work by making a tax deductible gift through NYFA here: https://www.artandobsolescence.com/donate

Transcript

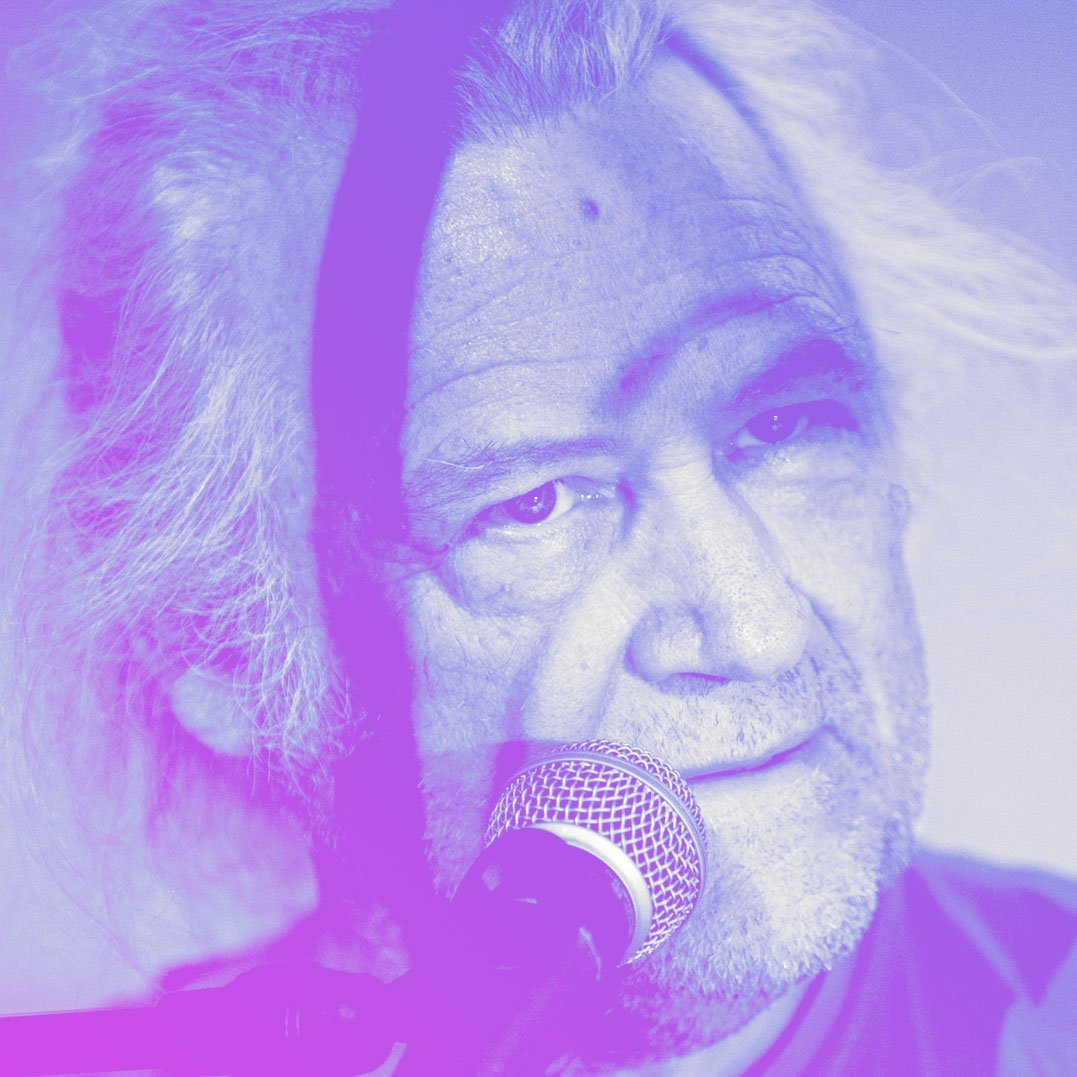

[00:00:00] B.: From small data industries, this is art and obsolescence. I'm your host B. Fino-Radin and on this show. I chat with people that are shaping the past present and future of art and technology and on today's show, we are closing out the year with an all-star lineup of artists. We are revisiting conversations from 2022 with Gary Hill, American Artist WangShui, Meriem Bennani, Alan Michelson, Tormaline, Arthur Jafa, and Hito Steyerl. What a list. I don't think I say this enough, so if you'll all indulge my inner fan girl for a moment. I just want to acknowledge how lucky I am that I get to visit with these artists and share our conversations with all of you. I've been doing my thing in my little corner of the art world now for over a decade, but I still can't believe that I get to do what I do. I honestly have to pinch myself sometimes when I hear back from these artists confirming that they'd like to come on the show and I have so much gratitude that I get to build relationships with artists that I personally admire so deeply and in that spirit of gratitude, I'd also like to close out this year by thanking all of you that have supported the show over the past year, seeing a community and audience organically develop around this very DIY show, and hearing from all of you has been so rewarding. And thank you, of course, to all of you that have supported the show financially this year, you have made these artists interviews possible. And an extra special, thank you, especially to the Kramlich Art Foundation for their generous gift in 2022 to support 10 new artists interviews. Many of which are still coming in 2023. In fact, as you're listening this week, I am on the road, visiting Providence, Rhode Island, where I am doing an in-person on camera artist interview. In collaboration with the great folks at VOCA Voices in Contemporary Art. So stay tuned for that in 2023 can't wait to share that with you. Lots of exciting stuff in the works for the next year, but until then, let's dive in and revisit some of this year's great moments on the show, kicking things off with Gary Hill. Back when Gary and I spoke, we had just wrapped up a conservation project on a video sculpture of his, from the nineties. And we were just embarking on a new major conservation project on his 1992 interactive video installation, Tall Ships so having had some firsthand glimpses at how Gary thinks of the materiality of his work and the technological obsolescence, I was really keen to dive in deeper with him on this point.

[00:02:27] Gary Hill: I mean a lot of us is flux a lot for me. When I think of a video installation or a media installation I really prefer almost the notion that an installation is kind of like a performance and, there's a history of performances and some people perform better than others. But also that the most important part is, that there's a kind of score. In other words, it's much more like a musical score to me. If you think of like, you know, a Bach work or something. Bach would be interesting because he wrote works for clavier before the piano, and now people play it on a piano, which is totally different. Yet when that person plays it or another conductor conducts a symphony we can still say, oh, I know that work. I know what that is. So I mean, that's very basic, but I think that's the beginning point that I see is the way to think about it. And so when someone says, yeah, but that's not the original monitor, they're barking up the wrong tree for me. I mean, this is completely nuts. For a handful of works that are CRTs in that description would, would be a particular quality of that physical object. And that's where it gets sticky. I wouldn't say across the board, it's cool to replace all CRTs with LCD displays. But I also wouldn't say that this is not allowed. It may be not allowed now and we don't know what's going to be available later. I mean, there might be some other thing. There's kind of an idea that came to me because of this problem, like say for a work like, In As Much As It Is Always Already Taking Place, there's 16 CRTs ranging from a half-inch, one inch, three inch, two inch 6, 7, 9, 12, whatever, up to 23 inches. So even right now, you know, to replace that still could be done today. You can find it. This is almost like a archeological process. I did another work kind of about this issue and it's called In As Much As It Has Already Taken Place, which has the same space as the first with the same sized, just blown glass though, you know, they look like CRTs, but there's no images, there's no wires there's no nothing. It just looks like an excavation of a ghost of that previous work and it's made 30 years later so then I thought, wow, you know, what if, what if you were to project on this? The faces are sandblasted. Would that be acceptable? I don't know if it is or not yet, but that's an interesting idea even actually, to do a work that has nothing to do with either one of those. There's an irony involved in projecting on a simulated CRT and it would create a different texture actually altogether. I kind of want to write, what do they call it? Like a white paper on each work you know, kind of branching out? Almost like you're following the thought process. Even if I don't have the answer. At least there's a detailed attempt at what it means and how to maintain that, you know? So Yeah, to me, it's still, I don't have an answer. If I make good enough art, you know, there has been paintings that cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to conserve. Right. You know, at that point, you can make CRTs for a price. I mean, people can do it. So if culture wants it, if they think it's saying something and and continues to say something, they'll pay for it.

[00:06:18] B.: Now you don't have to be practicing as long as Gary to have encountered conservation issues, as we heard in our chat with American artist.

[00:06:27] American Artist: Oh my God. Don't even get me started. I made this piece a few years ago called Sandy Speaks and it's this chat bot that was, you know, inspired by what happened to Sandra Bland. The woman that was pulled over in her car in Texas and she was taken to jail and ultimately she died in jail and it seems that the police most likely had something to do with that, but then it was kind of like covered up or presented as like a suicide. But this piece was responding to her and her legacy. It was this chat bot and it used this platform. And, the user side interface, you know, it was something that I had developed and programmed. If you've tried to make a chat bot it's very hard because the amount of language you need to anticipate and be able to present in order to produce a realistic conversation is like way more vast than you would imagine it is. I'm sure those systems are, better now for someone, you know, working on a small scale of trying to make a chat bot but at the time it was really difficult and so that was like one aspect of it. I was just kind of disappointed in the performance of the bot, but also just in the, in the maintenance, like every time I want to show it, I have to do some work on it to make sure it's like working. And I had this other piece, this sculptural work called The Black Critique Towards Wild Beyond, and it has these cell phones that are playing these videos, like several of them and they're like plugged in and there's like, lights. It's really a complex object. And yeah, it's just really hard to like, communicate how it works even like I wrote like a manual for it which is so many pages long. And even then I feel like this is so complicated and it's because it's work that requires, you know, specific software or technology and it just made me feel like, you know, I really enjoy making work like this, but it's so hard, the maintenance, you know, is like really complicated. So it's made me like reconsider what kinds of pieces I make and if I take a risk like that and do something really complicated, I'm now thinking, you know, okay. What about after the show? What about all the shows after this? What if someone collects it? What if a museum wants it, you know, all these things that I wasn't thinking about, you know, a few years ago. And so if I do make something complicated, I have to like anticipate that there's going to be a lot of work going forward in relationship to those decisions. One thing that I think I did learn from my brief internship at a gallery. I was writing manuals for how to update their website. Very long manuals so that kind of like gave me a precedent for how to make a manual for maintaining a work. I think how my brain works kind of lends itself towards this kind of activity, describing in detail how you're going to put this together. So that's something that I've like begun doing, you know, writing the installation instructions. It's very time consuming, but, that's sort of become at this point, at least this is like a normal part of making a work is being able to describe to someone else how it's going to be maintained, how to put it together. I feel like many of my technological choices are because the ideal that I would want isn't possible for me in that moment, you know? So in that sense, that specific technology is not important for the concept, but at the same time after I've like, you know, spent the time developing this. Now I have an emotional attachment to it. So I kind of do want it to be kept like that.

[00:10:14] B.: This question of documentation was a common thread. As we heard in these two clips from our chats with WangShui, and Meriem Bennani about creating documentation and manuals for their ambitious installations.

[00:10:29] WangShui: I rarely have the time or capacity to even consider conservation, but the first time I thought about it was when the Walker Art Center acquired my piece Gardens of Perfect Exposure. It was the first time I was asked to really put together a manual, which was really intense because the work has so many moving parts, including live silk worms. I'm really terrible at spreadsheets and itemizing anything. I tried to really walk myself back through process of creating it. And a lot of it is constructed onsite in the installation space. I honestly kept thinking they were for sure going to cancel the acquisition when I was writing the manual, but somehow they didn't and were actually extremely patient and understanding about it which was very surprising to me personally, because I think of all of my work as a headache, because it's usually so unwieldy. I like making it, but after thinking about what's going to happen to it, or even packing it up is always like overwhelming for me. I guess, with the new AI works, they are very, very technically complex and also physically complex, and I don't know, I guess so far it seems like collectors and institutions are a bit intimidated by them. When I was installing the work at the Whitney they had this registrar that was just taking photos of everything we did and writing it down and I was like, wow, I don't live my life like that at all. I just kept thinking to myself like, good luck with this one. On one hand, I honestly feel more concerned about the survival of the planet than my work necessarily, but in another hand, I think, there's a theoretical physicist I really liked named Carlo Rovelli, who talks a lot about entropy and how space, time doesn't even exist it's just a series of events, so even objects around you, they're constantly in a process of entropy, even if you can't perceive that timescale. So there's part of me that knows that all of my work is already disintegrating. So that gives me a sort of freedom in a way and so if someone else wants to maintain it as an object and fight quantum gravity, then they can go for it. Not that I don't believe in the conservation of art, on the flip side of what I was saying in my fantasies my work outlives our species and is picked up one day by a different species and can say something about the time that we lived in. Which is the reason why I feel this important kind of responsibility to kind of speak to this moment of human machine evolution that I think we're undergoing. That's why I keep calling them cave paintings. These metal shards will be found in a fire, but they'll be etched into the surface and they'll see like a reflection of something.

[00:14:04] Meriem Bennani: I felt like I worked for Ikea, making like a manual. It's so boring, but actually once I started doing it, I get really into it. I like that part of my work actually. Whenever I do an installation or a sculpture I draw it all in the 3d program and I love the part where I make a full PDF with everything mentioned, materials and, I do like those aspects. They feel almost calming and meditative, like doing the dishes, you know, like you don't have to come up with creative decisions, which is the most difficult thing. You're just being precise and trying to communicate something so that it can be as close to possible as what you want. And what do you realize really fast when you make a manual is you think about your death. The first thing on the page of my manual. If I'm alive, or like, if I'm around, or able to come install at preferred that you call me and I come do it myself. I'm really bad at delegating, but otherwise here's a manual and I say that because for example, you know, Party on The Caps, you referenced, the Stoschek installation. So that actually is an installation that I first made for the biennial of moving image in Geneva in 2008. And then it traveled to Turin and then it traveled to Stoschek, and then there's the version also that I showed at Clearing, my gallery in Brooklyn and we rebuilt it because that first version was in Europe, you know? So we made a new iteration, so, you know, every time it looks completely different. There's a few elements. It's kind of like a pieces of a puzzle, they can be arranged differently. And I love like re-drawing them to look completely different every time, to be site-specific and different. So, for example, as Stoschek, there's these big columns in the middle of the space that are very challenging for installation, I just decided to project on them and bring them into the installation. So if you follow the manual, it will look like my work, but if I can be there, I love the idea that I can always change stuff, you know, and like use the architecture differently. Or sometimes I add a screen that's a rear projection. Sometimes I add like messages in the back, little things that, like, as you go through space feel wording to find, and special and add to the world, because it's so much about world building with the Caps project, for example. I am not good at small-scale I think. Even like when I draw, I can't draw on a small piece of paper. I have a pretty like dramatic or like, YOLO kind of personality when it comes to scale. Like, if I have a party, I like to invite a lot of people. If I make food, I'll make a lot, you know, like, if a screen can be as big as possible and like, maybe that's tacky, but I love it because if it's going to be a show and you come out of your house, I like to experience that it feels different, or exciting, in these very, maybe childish ways. I love installing and like, I always forget it until like I'm back on an installation and I love feeling the architecture and making sculptures, you can sit in and like, creating these physical elements that add to the experience of watching the video. I think that's like a very fun space for me. And of course, you know, I'm very comfortable online. But I don't want that to be my goal. I ideally would love to keep making exhibitions that have a very kind of physical implications, you know, like that make it interesting to leave your house, to see a space or have an experience, you know, but if I didn't do that, if I make film, which I really am focusing on right now, and it's really like what I'm excited about, I don't want it to be little videos for social media platform. I want to make, you know, movies that can be seen properly or like, or ripped and like, seen by everyone, but not for a platform. I think the challenge, not in terms of conservation, but like in general is a lot of sculptures I've made and installations are way too complicated. I always tell people I'm like, I'm sorry in advance and they're like, oh, it's totally fine, and then like three days in they're like, oh my God. It's very complicated and I feel like I need to kind of simplify things. That's why also I took a break from the multiple channel. Every time I have to install it, it's like doing a full new show. And I was like, if I just toured all these installations. I wouldn't have time to make new work ever, unless I did the thing where I send people. So the conservation challenges in terms of file formats, I'm really interested in what people, you know, conservators kind of like project in terms of formats. And what's really interesting is to see that we really have no idea what we were talking about. I remember, one of the first time I sold a piece to a museum or a piece ever, I went to the conservator, with my little hard drive I was just like, so curious, you know, cause there's like different video files and I gave them an After Effects project cause that's where I do my mapping and then he was like, okay, no way, it can't work like that. So I had to, be like, okay, I can only, give the video files and they have to do the mapping on whatever program they want. They don't have to use after effects like me. It's just so crazy that we are, depending on these decisions, you know, in terms of the file formats we use. What I wonder is like, is a conservator thinking of 20 years as like a half second, like what scale are they thinking about? I think I started dealing with acquisition logistics right after they stopped asking for artists to have a Beta tape, you know, there's so many questions that feel very obsolete. But I find it helpful for them to say like the ideal way that you want to show this mostly for my single channel, because my installations it's like, self-explanatory, they need to be installed for the single channels. For example, I really don't like them to be on TV screens in headphones. I like them to be like a certain minimum size. So I'm happy to be able to just express that.

[00:19:54] B.: In our visit with Alan Michelson, he walked us through a few of his installations, and then we delved into how he thinks about questions of site specificity.

[00:20:05] Alan: I had an idea that had been kicking around for a long time, which was to do something that related to New York as a site of Lenape, habitation and also certain practices vis-a-vis the environment which included, fishing for oysters. And then the middens, these monuments really these large piles of shells that they left over eons, most of which have been destroyed bulldozed away or burned for lime. That was actually a big thing in New York at one time. The way that I originally found out about all this stuff was a piece I did in 1989-1990 for, the Public Art Fund it was a piece actually that brought me back to New York where I've been ever since. And, I was looking at the disappearance, the erasure, the poisoning and burial of a large freshwater lake that once existed in lower Manhattan. On one of its banks was one of these large shell mounds, these middens. It was large enough that the Dutch actually had a name for it. The Dutch called it Kalck Hoek, which meant sort of shell point our lime shell point. It was something that had built up over time. So I imagine that many people would be eating, you know, it was a very social idea of first of all, fishing a collective pursuit and then the cooking of the shells and consumption, and then just leaving them in this huge pile. So I imagine it was a good, 50 or a hundred feet long, Again, imagine that the Dutch having a name for it and there was a large Promintory actually that wasn't a shell mound. It was just a natural feature that was about a hundred feet. That was also just bulldozed as fill into the pond at the time. And that we're talking like, early, early 18 hundreds, like maybe it was all filled by 1811 or something like that. Anyway, in the spirit of that. I wanted to get out in a boat, which I've done in other works beginning with a work I did in 2001 for a show at the Queens museum where I sailed up a very polluted Creek, Newtown Creek that divides Greenpoint Brooklyn from Long Island City, Queens. And I shot all three and a half miles, of it's Queens shoreline from a boat and a boat, you know, on a calm water makes for the most amazing dolly shot. It just looks so good. I'm interested in some of the early movement from artwork that was easel painting, or murals, to panoramas, which happened in the very late 18th century and extended into the 19th century and panoramas were really the most popular art form of the 19th century in Western European countries and in the United States. There were buildings built to house panoramas. It was a sort of theater and some of them were in the round and some of them were actually there was a form of Panorama that was called a moving Panorama where it was painted on they used to call it miles of canvas. So imagine, a 10 foot high thing of canvas onto a big roll of it. The subjects were things like river journeys you know, a voyage down the Mississippi river or you know, a whaling voyage around the world, were typical subjects and people would come in and sit and you'd get the illusion of moving in a ship, on a train or something like that. And they would have sound effects and they'd have somebody narrating the whole thing, you know, it was sort of like national geographic special, but, done with canvas and paint and shaking a sheet of tin to make the sounds of a storm, or there'd be some sort of drama. So to get back to where I wandered off from, I like getting out in boats. Unfortunately, most New Yorkers don't get to see it's shorelines and there's something like 600 miles of shoreline in and around New York. And you see a lot of stuff that's beautiful and expected, and then you see stuff that isn't and you see this odd mix of, you know, nature trying to survive in this heavily urban environment with all sorts of pressure and pollution and everything. So, I partnered with the billion oyster project this amazing nonprofit on Governors Island. What they do is just amazing. They collect oyster shells from area restaurants. I think they have over 50 that they deal with. And then they deposit them in huge piles, which cure in the sun for a year or so. And once they're clean they essentially bale them in these sort of wire cages and strategically build oyster reefs out of them and the Harbor. Oysters attach themselves to a hard surface. So it becomes habitat not only for oysters, but for, um, other fish, including the fish that eat oysters. And so an oyster apparently can clean up to 50 gallons of water a day. And so their ultimate ambition is to put a billion oysters in the Harbor, they may never again be edible, but the Harbor can sure be cleaner and it's already cleaner because of them. Anyways, I saw a relationship between the Lenape's, environmental sort of practices, I guess you'd call them now, but they're really cultural practices to o where you're in relation with the living non-human world, with non-human life you're in a kinship relationship, not one of domination and exploitation, or extraction per se, and so, I just thought that it would be interesting to, sail back into Newtown Creek, which was once a really good oyster ground and also to the Gowanus, which is now being developed, and was also apparently an amazing oyster ground where they pulled out oysters, even in the 16 hundreds that were like a foot long. It was sort of absurd in a way to sail past these shorelines that no longer supported oystering, or that kind of life that had, you know, long, long been destroyed there, and just to see what's there now and then to project those images, those shorelines onto an actual bed of oyster shells. And in that collision, you know, in that marriage one starts to take on maybe the properties of the other. So the video tends to become in a way more solid in some respects and the oyster shells become more sort of liquid. Ruba Katrib and her amazing team at PS one allowed me to put it in the duplex gallery, which is if you're familiar with it is a two story gallery that actually has almost like a third sub story a sort of sub-basement it stretches from the basement up through the first floor up to the second. And so this piece, which was arranged in a, long linear rectangle of shells that was close to 30 feet long and about, I don't know, seven or eight feet from its edge to the wall and rose, maybe about 18 inches, something like that, maybe below two feet, sort of sloped down from the high of 18 inches or two feet down. Down to the end. So it was a very long rectangle and I like to work again in that panoramic format. And projected the results of two of my sails onto it, and also supplied a very active soundtrack of five Akwesasne Mohawk singers singing the songs, there was probably about a dozen, that make up what we call our stick dance which was a set of songs and a dance that was given to us by the Lenape, the Delaware people. It's also known as the Delaware skin dance. The Lenape people when they were under terrible stress from colonization they didn't think they could preserve that element of their culture, so they gave it to us for safekeeping. I wanted it because it's really the sound of of this area. It's the sound of the indigenous people of this area. So all those elements together made the work and you could see it from the main floor looking down. They have two big openings that you look down. So then it sort of looks like you're looking, at something that's more or less flat, but that has all the texture of oysters. But then when you go to the basement, you see it from a slightly elevated perspective. So it's flatter. And then finally, when you go down the steps into the sub-basement, you can go right up to them and their materiality really takes over, the video just looks like colored water or something flowing over shell. That was a great project to work on. And typical of the way that I've been working not only in my good fortune in working with curators, who commission new work from me, but also collaborating with an institution like PS1 who were, down with this, pretty much from the start, loved the idea of partnering with another, amazing collaborator, the Billion Oyster Project. And even though I am a very small solo operation and have been all the time I've gotten to work with some amazing people over the 30 plus years in my career. I certainly have collaborated a lot over the years and it's been, uh, it's been great.

[00:29:28] B.: That's great. So. I'm curious how you think about variability in terms of your work, because you do a lot of these site specific installations and it seems like maybe there's a spectrum of level of site specificity, for instance the installation at PS1. Is that something you would consider installing elsewhere or do you consider these installations to be uh, fleeting moment?

[00:29:56] Alan: Yeah, that's a really good question. I think some of them can travel and some of them can't. Actually the greater New York one may travel. And the way that that would work is the shelves would be shells locally. So then it would establish a connection between good practices with the environment. It would make a connection between, you know, traditional environmental knowledge and practices of indigenous people here, and then wherever else it would be shown, you know? So in that case site is somewhat mobile. I'm open to a certain amount of variation in the iteration of my work, even with the blanket piece, the one that I am showing in Mountain Time it's the sort of second edition of this piece. The other one being in a show that Wendy Red Star curated for aperture that's currently in Princeton. And so, you know, I'm not so strict, I guess maybe I should be, but I'm not so strict in the edittioning that, you know, I'm going to have, like, three of the same blankets loomed at the same time, 1, 2, 3, I think, there's hopefully enough poetic or whatever license. So that the style blanket is the thing and a slight change in, size or proportion doesn't present a problem. So I think like that if this piece does travel I don't know what sort of options I might have. I'm usually open to finding a way to, preserve the work within a new, set of options and surroundings. But with that, I would think that you would need to really be able to see it, not only from your own height looking down at it, but from some sort of a height and then it would be a question of, well, how do you get that height? And there's all sorts of possibilities. There are atria I suppose, that are all around, that could be utilized. And then another thing would be to build something. Like a bridge that would be, elevated that you'd have to ascend and descent.

[00:32:02] B.: Part of what I love about doing these interviews is hearing about people's origin stories. And with artists I'm often keen to learn about where they picked up their skills and influences along the way. And as we heard in our chat with Tourmaline, she really picked up her filmmaking skills on the fly learning by doing.

[00:32:18] Tourmaline: My first time ever on a set was when I was directing Happy Birthday Marsha, I kind of just learned by doing, you know? And now looking back, I'm like, that's wild. I had literally never been on a film set until I decided to direct. But also, you know, like I think that many people who are like doing a thing that like they don't feel represented in, or aren't aware of like other people who are like them or have some kind of affinity with them. Like that's a frequent experience that so many people have. But yeah, like I learned it through doing it and you know, I had like teachers on set too like Arthur Jafa was the cinematographer for Happy Birthday Marsha, and was like a friend and, uh, and a mentor of mine and Sasha Wortzel, who was the co-director of happy Martha Marsha, you know, had more filmmaking experience than me and was really instrumental in my understanding of it. I picked things up like really fast as something that I've learned about myself. Because I'll like go so hard with it, it'll be the only thing I can think about for, X period of time is like making myself a better filmmaker. I'll spend, the hours on set, but I'll also spend the hours like reading the books or watching the YouTubes, or, you know, I also work for this filmmaker Dee Rees on this film Mudbound which we shot in Louisiana. And that was really like a powerful experience, you know? And so, yeah, I think all of it has been learning and watching how other people are doing it. Going to set when other people are directing things that maybe look nothing like what I'm doing, like I went to like John Wick set, and that was like so incredible, and like just watched Keanu Reeves do this like beautiful action sequence. It's also like the smaller, you can make something, when it's not this big, huge thing over in one place, but it's something that you're kind of continuously moving to and learning from and being engaged with until it gets to be like the next logical step of your process. That to me has been really helpful. For instance, when I was doing Mudbound, those were like 15 hour on set and it was just like, that's what everyone was doing. That was my film school, you know, just like these long ass days in the summer on a former plantation in Louisiana. And so you really quickly learn the language of it, you know, it's no longer this whole other thing over there, it's just your life. So that really helped me with the second big shoot for happy birthday Marsha. Like we did a whole nother like shoot after I came back for the film and then it also really helped me for you know, like Atlantic is a Sea of Bones and then Mary of Ill Fame. And I was also doing a few commercials in between and all of it, just had a major imprint on me and sometimes I'm really aware of being quote unquote, self-taught like not going to film school cuz there's some things where I, I just don't know the thing and I can learn it. And then there's other moments where I don't know that I shouldn't aspire to something cuz it hasn't been like drilled out of me. Like I desire to do X thing, you know, that sometimes schooling can do. And so yeah, it's been a really interesting path.

[00:35:42] B.: One of the biggest treats with these artists interviews, of course, is getting this sort of direct access to what artists were thinking about when they were making the work. And we got just this in our chat with Arthur Jafa.

[00:35:54] Arthur Jafa: It was in some ways a response to the response to love is a message, you know, I started to feel a little ambivalent about the kind of um, seemingly uncritical response to it, like positive response to it. The kinda overwhelming response to it just created a kind of ambivalency in me about the actual work itself. You know what I mean? I used to say it was like a kind of microwave epiphany about Black culture or the state of Blackness, you know, from the art world that I certainly never imagined. And in some ways it sort of actively pushes against the goals against some of my sort of fundamental understandings of the kinda inherently alienated quality of Black art and Black expressivity and Black people in general to society at large. You know what I mean? So there's a way where I started asking myself, like, is Love is the Message fucked up because too many white people like it, you know what I mean? So what's that about particularly something that figures or features so prominently, like Black death in it, you know what I mean? I started to have some real sort of ambivalence about it, so. Kind of very intuitively I moved towards making something that was very much antithesis of love is the message. There were no shortcuts. There was very little sort of, you know, Dziga Vertov-esque editorial sequencing, you know what I mean? It just feels very much like a mix tape or something that was just strong together, you know? I also like put it in a show and so my whole thing was like, this is evidence of Black expressivity at its very, very, very highest frequency. And I used to say, I would often look at it to just measure what I was doing against that. You know what I mean? To me, it required a certain amount of nerve to have an extended thing that had people operating at such a high level expressively. And have it in proximity with, the things I made, so to speak, and you know, and I was thinking about everything from Zidane you know, like Douglas Gordons and um, Philippe's film Zidane you know what I mean? Like, And Warhol and all the things that I always think about, and very much Gerhard Richter, you know, that E.V. Hill sermon in the very beginning of the film it's so blurry, you can't see what the people are doing in the wide shots. And I was like, yeah, it's like the Baader-Meinhof paintings. You know what I mean?

[00:38:27] B.: Yeah. Like 100% actually you touched exactly on, a kind of nerdy question that I have for you. One of the things that I've always wanted to ask you about that piece is, you know, you being a professional within the film world, a DP and a cinematographer, obviously you are highly attuned to image quality. But in that piece, you know, everything is appropriated of course it's ripped from the internet and it's highly compressed and there's a lossiness. So I was just curious like does that have any kind of significance to you or meaning in the work

[00:39:04] Arthur Jafa: Yeah, but on a very imminent kinda level, you know what I mean? It's not a deep thing. It's just, more indicative of my sort of very intense ambivalence about notions of quality. I mean, the most thought provoking, maybe productive thing any artist has ever said to me, That I remember as such was like in 99 or 2000, I was in the first international art show I was ever in. There's a show called Mirror's Edge. That was curated by Okwui Enwezor. And, um, when I went over to, Umeå Sweden for the opening of the show, I ended up on a panel and I was sitting next to Thomas Hirschhorn. And, uh, he said something I never forgot. He said "energy, yes. Quality, no." I've never forgotten it. You know? And I feel like oftentimes the things that people say to you that strike you are the things that are crystallizing, something that you're already thinking about. You know what I mean? And so that energy yes, quality no, is something I'm like committed to on a very deeply situated ideological and spiritual level. You know what I mean? So as much as I certainly have a very finely tuned sense of, you know, what technical excellence looks like in film terms, I feel like it's very expanded. You know, my favorite cinematographers would be like Gordon Willis and Néstor Almendros, like on one hand, but the same time, you know, I don't know if anything they ever did had as much impact as Scorpio Rising, where quality of the image has very little to do with any sort of technical quality of the image. You know, Kodachrome that film stock that he used on, um, Scorpio Rising is a phenomenal chaneler of energy or something, you know what I mean? That actual film stock, the way the film grain moves around the way the chromatic you know, construction of film, stock functions, all that's really incredible, but it's not like fine grained. It's not like IMAX or something like that, you know? So, I like to think that my interests in those kinds of things are almost, to reference somebody who I sort of have a love, hate relationship, mostly love relationship. Like almost you know, Peter Gidal-esque materialist film sorta take on these things. Like you take these things and you divorce them from any kind of objective hierarchy of image quality. You know what I mean? And you just take it as a material thing. I used to laugh you know, even as far back as Love is the Message, when people were saying to me, like, you know, we can get this clip without the logos, like the watermarks and stuff. And I was like, why? It's not gonna stop the film from functioning. And maybe it's cool, you know, that you can see that these things are reappropriated. Reappropriation, wasn't the point, but it doesn't mean I'm not utterly aware of that aspect of, you know what I mean? One of my central metrics of a work being successful is that it is discrepant, you know, Kerry Marshall said when I asked him, what's the difference between painting and photography. He said, discrepancy, and if you're reading Nathaniel Mackey's writing on discrepance and things like that, you see, like for me, the analogy I've always used, you wanna make a work. That's powerful enough that if a Muslim stood in front of it, they would fall to their knees. But if a Christian stood in front of the same thing, they would fall to their knees or Zen, Buddhist would fall to their needs. Like, how do you make a thing? That's not singular in its, um, signification you know what I mean? But is flexible and complex and dialectical and discordant and discrepant, as a thing can be, you know, and that to me is very much in keeping with certain aspects of Blackness ontologically, the mix. You know what I mean? The miscegenant thing, all these kinds of stuff. So to me, akingdoncomethas was very much always that, it was always like, a series of Gerhard Richter paintings, strong together at the same time, it's a music video and a music documentary and, uh, kind of, uh, sociological treatises, on, Black spirituality, uh, when one of my best friends saw it, the first person I actually showed it to first thing she said was like, if I didn't know any better, AJ, I would think you were a believer. And we both laughed when she said that, cuz she tells I'm not, I'm a heretic or heathen and um, so I don't believe in this, Judeo Christian theology or anything like that. I mean, even though I was raised in the church, as I said but I do believe in Black people, believing you know what I mean? So in some way it's a study of not what Black people believe, but how Black people believe, you know, which I think is at the core of a lot of what I'm trying to get at in my work in general, what is the nature of how we believe and what is that superpower? Cause I do think it's a superpower because I think our ability to be able to imagine something into actual being has been, in some ways, certainly a critical, if not , the key to our ability to be able to survive, the Americas, you know, our experiences as people of African descent in the Americas.

[00:44:33] B.: Now, I think I've shared this on the show before, but one of the things that I love about visiting with artists is how different the physical realities of everyone's studio practice are for some artists. It's just them in a laptop and others run things in a more traditional setup with a sort of physical space and assistants. And sometimes there are surprises. For instance, even an artist like Hito Steyerl who makes large ambitious and very physical and spatial installations. We learned in our visit with Hito that she doesn't see them at scale until they are installed for the exhibition.

[00:45:06] Hito: The steepest part of the learning curve was trying to. Figure out what the realization of some kind of 3D model might look like in reality, because obviously it's always different, but you need a lot of experience to be able to guess beyond that gap. I got a little better at guessing in the meantime, but usually we build it once. We build it twice, and the third time usually is when it gets to a point where we say, this is how it could remain in the future. The installations, many of them keep changing. For example, there is one called Liquidity Incorporated. It's a single screen installation which had half pipe element and. This completely got wrecked. I think after Trump got elected, I decided to wreck that part. So it's basically a wreck of a half pipe now. Yes. So that kind of thing can happen with installations. Sometimes we even find ways of improving them way after their premier, for example, the same work Liquidity Inc. Which some guys in Georgia, I mean in the Central European, Georgia, made a suggestion to show it under some sort of pier over the water, just suspending some screen. I thought it was a brilliant idea. That's even better than the way we installed it, but I wouldn't just install it as a draw for no particular reason. the contracts are stipulate that whenever anyone wants to show anything, they need to talk to me or us and basically come to an agreement over the form this is taking so I don't think anyone, It's probably happened, but in theory, no one could just go ahead and install something just as they please. Of course, it's a very historic. Contingent phase that we have very little control over how it will be preserved. But in the shorter term, I'm sure that the understanding of art will shift a lot and in not always predictable ways. One journalist colleague told me about recently because of the energy uncertainty in museums in Germany, there is no guarantee there will be climate control this winter, the insurance has become staggeringly expensive for these masterpiece, et cetera, to the point where it becomes basically no longer viable to even try to imagine paying that kind of insurance. These are very real factors that happen in the background that we don't really see on the surface that much as of yet, and which will no doubt contribute to the art world changing a lot, becoming much more vernacular and local and also parochial, unfortunately, I think in the next few years with a slightly reduced horizon, also backwards inclined. I think if someone cares about the work, then someone will take care of it. If no one cares, then it's maybe not worth preserving in the first. It's also very well possible that things are not worth pre preserving. Probably 98% of our artworks at the end of the day are not really valid 10 or 20 years after the day they were made. I think that's not a reason to worry. That's how it goes. the steepest part of the learning curve was trying to. Figure out how to, what the realization of some kind of 3D model might look like in reality, because obviously it's always different, but you need a lot of experience to be able to guess beyond that gap. I got a little better at guessing in the meantime, but usually we build it once. We build it twice, and the third time usually is when it gets to a point where we say, this is how it could remain in the future. The installations, many of them keep changing. For example, there is one called Liquidity Incorporated. It's a single screen installation which had half pipe element and. This completely got wrecked. I think after Trump got elected, I decided to wreck that part. So it's basically a wreck of a half pipe now. Yes. So that kind of thing can happen with installations. Sometimes we even find ways of improving them way after their premier, for example, the same work Liquidity Inc. Which some guys in Georgia, I mean in the Central European, Georgia, made a suggestion to show it under some sort of pier over the water, just suspending some screen. I thought it was a brilliant idea. That's even better than the way we installed it, but I wouldn't just install it as a draw for no particular reason.

[00:51:14] B.: Hito, thank you so much for coming on the show.

[00:51:16] Hito: Yeah. Thanks a lot for all these fantastic questions.

[00:51:19] B.: And thank you to all of the artists that opened up their studios and their practice for us on this year's show.

[00:51:26] Tourmaline: Thanks for having me. These were brilliant questions.

[00:51:28] Alan: Thanks for inviting me.

[00:51:29] WangShui: Thank you.

[00:51:30] Meriem: Thank you so much for having me for your very thoughtful questions.

[00:51:33] American Artist: Thank you. Thank you for inviting me. You've had some phenomenal guests on here, so it's really exciting to be part of this podcast.

[00:51:40] Arthur Jafa: Talk to you soon. Peace.

[00:51:42] Gary Hill: All right. See you later.

[00:51:43] B.: And I'll see you later, next year in fact, dear listener. In the meantime, happy holidays, I am wishing you a great end of the year. Until next time, take care of my friends my name is B. Fino-radin, and this has been art and obsolescence.